Listening is Caring

Our family recently received a tough diagnosis. Our kids’ grandmother, my wife’s mom, my mother-in-law (who finally asked me a few years ago “Why don’t you call me Mom?”), one of the kindest, most conscientious, loyal, good-natured, servant-hearted and Jesus-loving people I have ever met, was diagnosed with stage-4 pancreatic cancer.

Two verses that are right next to one another came to mind.

“Many are the afflictions of the righteous.” (Psalm 34:19)

“The LORD is near to the brokenhearted.” (Psalm 34:18)

Walking through pain and suffering is a bridge over which every family must pass. We want to care well for the people that we care about.

What’s not always recognized is that it can be hard to know how to care well. And if we’re not aware of the difficulty – that despite our good intentions we often don’t know how to care – then we can end up adding to the pain we are trying to relieve.

No doubt you’ve had the experience of well-meaning friends and family saying things that inadvertently twisted a blade. Proverbs addresses how not to care for people in pain:

“Whoever sings songs to a heavy heart

is like one who takes off a garment on a cold day.” (Prov. 25:20)

The song may be true and precious, but sung at the wrong time or in the wrong way, it can end up intensifying the distress – like taking off one’s garment on a wintry day.

Many years ago, I knew a man who was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s in his early 50s. It was awful to see this once vibrant, brilliant man slowly lose touch. A local pastor faithfully visited the man’s family. His intentions were to care. But one day the man’s wife called me and said, “I swear if that man quotes Romans 8:28 to me one more time I’m going to strangle him!”

Romans 8:28 reads, “And we know that all things work together for good to them that love God.”

Not that everything that happens is good, but that God can create good out of everything that happens. It’s a precious promise that has consoled millions. But to recite Romans 8:28 to a distraught family is the wrong song to sing. Proverbs speaks to this as well.

“Whoever blesses his neighbor with a loud voice,

rising early in the morning, will be counted as cursing.” (Prov. 27:14)

The right thing (a blessing) said in the wrong way (a loud voice) or at the wrong time (early in the morning) becomes the wrong thing (a cursing).

So, how do we care for people who are in unspeakable pain? It’s good to start by reminding ourselves that our impulse – I don’t know what to say – that’s right.

Do you remember how the Bible speaks of Job in the first chapter of Job? The LORD says, “There is none like him on the earth, a blameless and upright man” (Job 1:8). And do you remember what Job says of himself in the last chapter? “I had heard of you by the hearing of the ear, but now mine eyes have seen you; therefore I…repent” (Job 42:5).

If the very best of us, by the Lord’s own reckoning, can say, in effect:

I thought I knew. “I had heard of you by the hearing of the ear.” But I didn’t know. I didn’t know what I was talking about, until devastating suffering brought me to the place of rethinking everything I thought I knew. “But now mine eyes have seen you…I repent.”

And do you remember what the LORD says to Job when the LORD finally speaks? The whole book Job had been demanding an audience, crying out for the LORD to explain why this has happened to him. Silence. Finally, the LORD speaks, “Who is this that darkens counsel by words without knowledge?” (Job 38:2). Eugene Peterson paraphrases “Why do you talk without knowing what you’re talking about?”

If the very best among us must be brought to the place of acknowledging he did not know, until he passed through an unimaginable furnace of human suffering, then perhaps the rest of us can put a hand over our mouths and resist the impulse to try and make sense of our friend’s grief. We forget that, for all their flaws, Job’s friends initially got this right. Consider what they did at first:

“When Job’s three friends heard of all this evil that had come upon him, they came each from his own place…They made an appointment together to come to show him sympathy and comfort him. And when they saw him…they raised their voices and wept, and they tore their robes and sprinkled dust on their heads…And they sat with him on the ground seven days and seven nights, and no one spoke a word to him, for they saw that his suffering was very great.” (Job 2:11ff)

No one spoke a word for seven days. If you’d been eavesdropping through the wall, the only sounds you would have heard were the sounds of weeping. Job wept. His friends wept. They wept with Job, and they wept for Job. Much later, when the Apostle Paul listed out the attitudes and actions that should mark a true Christian, might he have had this scene in mind when he urged us to “weep with those who weep” (Rom. 12:15)?

There’s care in sitting beside and weeping with. There’s power in being fully present with someone in pain. More important than what we say is how we show up.

Years ago, I had the privilege of training as a Trauma Chaplain in the Emergency Room and ICU of a large hospital outside Philadelphia. I was ill-equipped for such a charge, but my mentor, a 4’8” Franciscan nun named Sister Joan, proved to be a giant of caregiving.

She wore braces on her legs, remnants of the polio that had stricken her as a young girl in the days before vaccines. She got around the large hospital on a Rascal, one of those motorized scooters. She had a quick smile, a joyful countenance, and the gentle touch of someone deeply acquainted with sorrow.

She told me something I’ve never forgotten, though it’s taken me the better part of 25 years to begin to understand it. She said, “A person will look up from their bed and, in a matter of seconds, before you open your mouth, they will decide if this is going to be an important conversation, befitting the moment, or whether it’s just going to be a cordial exchange between a patient and a chaplain.” She added, “It won’t even be conscious. But they will decide. They will make up their minds before you ever open your mouth. Just by looking at your face.”

I believe she was trying to tell me that you can only be of help to others to the measure you’ve accepted help yourself.

Your compassion, your shared understanding, will be written on your face. Or not.

If we want to be available for others in their pain, we’ll need the fruit of time spent in solitude and silence, allowing the LORD to meet us in our own pain.

Because it’s when Job’s friends start talking, on the 8th day, that they get into trouble and become “miserable comforters.” Very religious. Pious. Well-intended. Windbags. It occurs to me that the Lord’s question to Job, “Why do you talk without knowing what you’re talking about?” is a good one for any Christian who dares to speak on the Lord’s behalf.

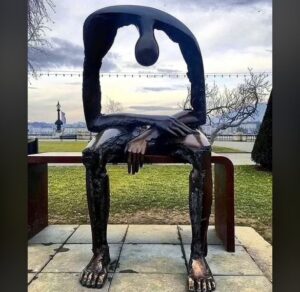

A friend going through an excruciating season of hurt recently sent me a picture of a sculpture.

“Melancholy” by Romanian sculptor Albert Giorgi.

He noted that it is cast in iron. The head is downcast, the hole in the middle is fixed – which is how grief can feel, like we will never get over this, nor should others expect that we would.

How might we care for this person? I studied the image for a long time before I recognized there was a space on the bench. Perhaps, if he or she wouldn’t mind, we could sit down beside them.

Job’s friends initially got this right. They came alongside. They sat with their friend and entered the rituals of grieving with him. They “tore their robes and sprinkled dust on their heads.”

We’ve lost something in our culture as we’ve largely given up our rituals of grieving. Ancient cultures (and some cultures still today) had professional mourners. They understood that sometimes we need others to give us permission to feel deeply, to wail, to let it out. But so many things in our Western culture conspire to keep us from our grief or rush us through it.

Have you ever been in a space – a funeral home, a hospital room, a bedside – where someone was crying out, heaving and sobbing in pain? Have you witnessed the healing of seeing a small community gather around, to touch and wordlessly console?

In the church, because we want to be of some help or comfort, we might feel tempted to offer some words of encouragement and consolation. Thank God for overly graciously people like my mother-in-law, who appreciate the spirit behind the effort, even when it’s clumsily delivered.

Don’t let your fear of saying the wrong thing lead you to a mistake just as grievous – avoiding, not showing up, saying nothing.

But as a rule of thumb, try not to meet the moment with a word of wisdom or advice. If your friend dares to ask their version of Job’s question, “Why has the LORD allowed this?”… let it sit.

Perhaps there are responses. But if Job “did not sin” (1:22) in his anguished complaints; if David, the man after God’s own heart, could feel forsaken (Psalm 22:1); and if even our Lord Jesus would take David’s words on his own lips, then surely there can be, there should be, a sacred space for silent presence.

We want to comfort. We want to reassure. But beware of the temptation to respond to an expression of emotion with a solution or a “bright side.” Instead of trying to talk your friend out of how they feel, far better to listen attentively and validate their feelings.

Yes, it’s uncomfortable. Grief is uncomfortable. And what do many of us do when we don’t know what to do? We start talking. But has it occurred to us that we are most likely speaking to make ourselves feel better, as opposed to making them feel better? It’s hard to sit in this awkward space, especially if we’re not in touch with our own emotions.

Don’t we need more than someone to listen to us? We don’t need less.

Henri Nouwen wrote, “To care means first of all to be present to each other. From experience you know that those who care for you become present to you. When they listen, they listen to you. When they speak, they speak to you. Their presence is a healing presence because they accept you on your terms, and they encourage you to take your own life seriously.” It’s so rare to have someone truly listen to us. Listening is not just about being quiet; it’s about being present. Listening is caring. Listening is an act of love. Listening is healing.

It’s taken me the better part of three decades to understand what Sister Joan was trying to tell me, that we can communicate a shared understanding without needing to open our mouths.

As Rick Warren said after the death of his son to suicide, “The greater the tragedy, the fewer the words.”

Next time you encounter someone in deep pain, remember what Job’s friends did right. Resist the temptation to solve or to fix. Pastors, recall that if Job didn’t know what he was talking about, and he was the very best of us, then maybe we don’t know all that we think we know.

Call to mind Giorgi’s sculpture and that space on the bench.

This is a new way for me to care, and I imagine it is for many of us.

This essay is dedicated to Russ Bartmus, who listened to me day after day, week after week, for years. He resisted countless opportunities to correct. He had much to say but knew it would have just bounced off me until I got all those words out of me. So, he listened. And then he listened some more. How does a mistrustful heart begin to let down its defenses and learn to trust? Consistent care, over a long period of time, through the sacred gift of listening. I’m just now beginning to understand, Russ.